How earthquakes work

Poster-Presentation “How earthquakes work” at CMCK

How earthquakes work

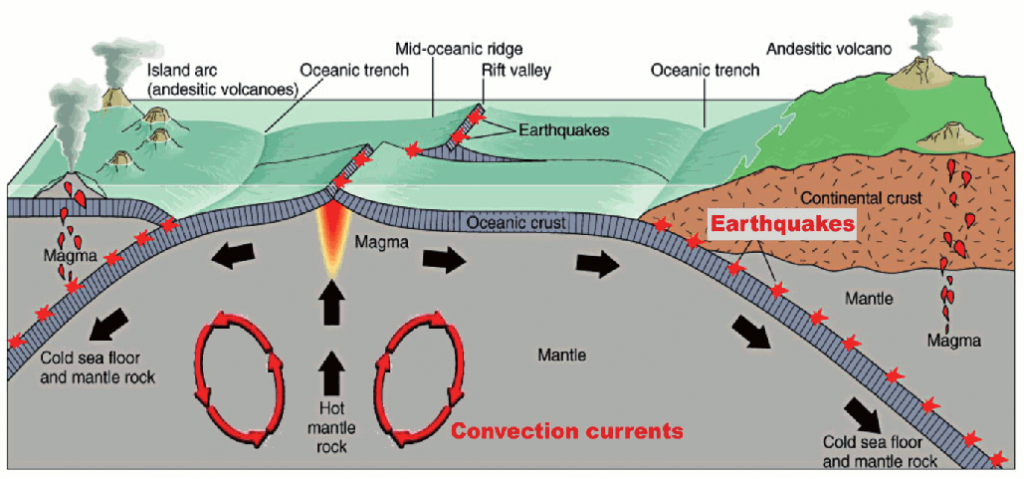

An earthquake is a sudden motion or tremor in the earth caused by an abrupt release of energy. We notice it, when the earth surface vibrates and displacement along ruptures occur, created by the earthquake. The source of the energy is the sudden movement of crustal blocks along fault planes, when accumulated strain is re- leased in fractions of a second. The overall cause is the movement of tectonic plates across the Earth’s outer shell. Additional sources of earthquakes are volcanic eruptions or even human-made explosi- ons. The outer shell of the earth, or lithosphere (earth crust and solid part of the mantle), is made up of a number of rigid segments called tectonic plates. These plates are continually moving at rates of a few centimeters per year – the speed of growing fingernails, driven by forces deep within the earth. Underneath the rigid lithos- pheric plates, the asthenosphere and the lower mantle (660-2900 km depth) behave like a highly viscose fluid, where heat from the earth’s interior is transported to the outer parts along large convec- tion cells, very similar to hot water in a kettle, but on a much larger time-scale. Scientists believe that the convection cells reach to the mantle-core boundary, but are not sure yet how many layers of con- vection cells exist.

boundaries (After: The McGraw-Hill Companies)

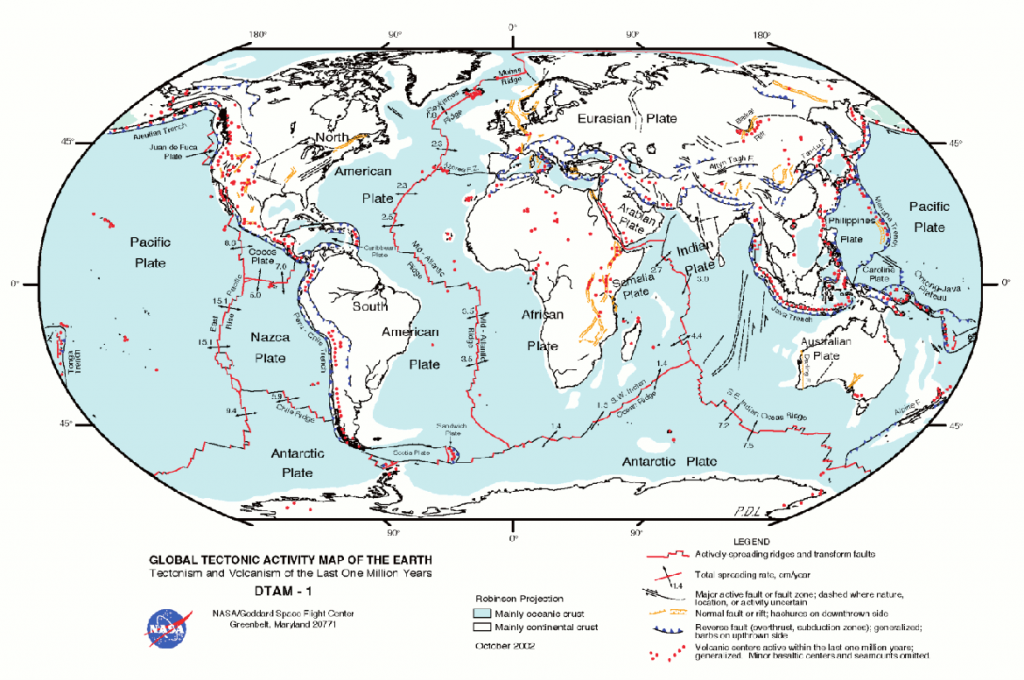

The earth’s lithosphere is divided into around eight major tectonic plates and a larger number of minor plates. Many plates are cons- tantly growing, at mid-ocean ridges or rift valleys, or consumed at subduction zones (ocean trenches). Along boundaries, plates are moving towards each other (destructive, convergent or collisional margins), away from each other (constructive, divergent boundari- es or spreading centers) and/or past each other (transform, trans- tensive and transpressive boundaries). It is along plate boundaries, where tremendous stresses build up, which, upon sudden release, result in earthquakes.

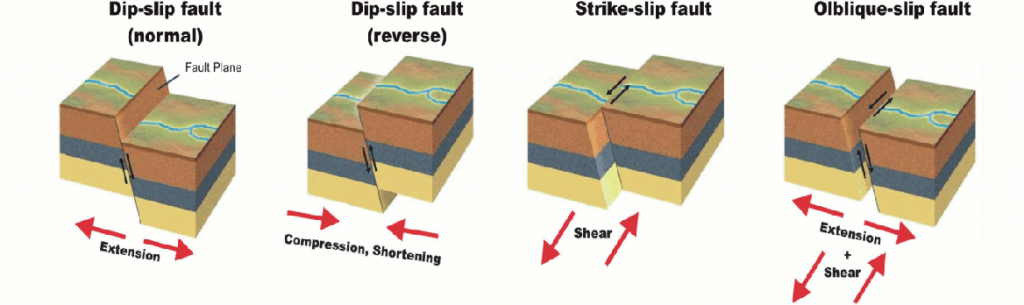

A fault is a rough surface where shear fracture occurs; the rocks on one or both sides of this fracture surface have slipped along each other. Faults can be divided into three major types: normal, reverse or thrust and strike-slip. Along normal and reverse faults, movement is in the direction of the dip (=inclination) of the fault plane, either down (normal) or up (reverse). Normal faults are generally active in areas where the crust is being extended, at a divergent boundary, e.g. a rift valley. Shortening of the crust, along converging plates leads to compression and blocks of rocks move over each other along reverse faults. Strike-slip faults are steep structures where two blocks slip horizon- tally past each other along the fault. In reality, most faults are a combination of both dip-slip and strike-slip faults, known as oblique slip. Thrust faults are generated by the highest, strike slip by intermediate, and normal faults by the lowest stress levels.

Text & Layout: Anne Kött